This lecture is an advanced tutorial of React and studies using SVG, Scalable Vector Graphics with React. React is a library for developing user interfaces. It has two primary features for enabling user interface. The first feature, the JSX syntax and compiler permits developers to put the HTML code in the JavaScript code. This makes developing dynamic websites much easier than older technologies such as JQuery. The second feature, the use of “state” to express the app and two way binding of the state with the application views. Using a state variable assures consistent app behavior, and with two way binding making a dynamic app is easy.

SVG is a markup language for describing two-dimensional scalable graphics. SVG is integrated with HTML and is compatible with all modern browsers. It is a compact and natural markup language to describe basic shapes, such as circles, rectangles and squares. And CSS can be used to define attributes of the shapes. SVG also integrates well with React making it a natural choice to manipulate graphics in the user interface.

React References

This Lecture assumes that you have a basic understanding of React. As such, you should have studied the “Tic-Tac-Toe” tutorial:

https://react.dev/learn/tutorial-tic-tac-toe

Also you should have read the articles about “Managing State”:

https://react.dev/learn/managing-state

In particular, the “Scaling Up with Reducer and Context” article:

https://react.dev/learn/scaling-up-with-reducer-and-context

You will also need to be acquainted with with the “Escape Hatches”:

https://react.dev/learn/escape-hatches

You will need to know how to get references to a node:

https://react.dev/learn/manipulating-the-dom-with-refs

Also we will need “Synchronizing with Effects”:

https://react.dev/learn/synchronizing-with-effects

SVG References

This tutorial also assumes you are acquainted with SVG markup:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG

The MDN tutorial “Introducing SVG from scratch” is a good place to learn SVG:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG/Tutorials/SVG_from_scratch

Fortunately, the application does not use advance features of SVG, so it will be sufficient to read chapters:

- Introduction: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG/Tutorials/SVG_from_scratch/Introduction

- Getting started: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG/Tutorials/SVG_from_scratch/Getting_started

- Positions: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG/Tutorials/SVG_from_scratch/Positions

- Basic Shapes: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG/Tutorials/SVG_from_scratch/Positions

- Fills and strokes: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/SVG/Tutorials/SVG_from_scratch/Fills_and_strokes

Client & Developer Goals

Our client desires that we implement an application which simulates in the browser hitting obstacles while the user moves the cursor from the start location to the target. Naturally, we cannot simulate exactly the feel and consequences of a “human hand” hitting an obstacle while reaching for a target without a “special” mouse that pushes back on the user’s hand. But, we can simulate some annoyances of hitting an obstacle, such as recognizing that a collision has occurred and delaying the movement during the collision. So, our goal is to develop several alternative obstacle collision simulations for our client to evaluate.

The Basic Technique

We need the app to have control of the cursor location and move it to the x/y position in the browser window which is related to the x/y position expressed by the mouse but not necessarily the same position. To keep track of these different positions, we need precise terminology.

Terminology

- Pointer location – is the position in the browser window expressed by the mouse.

- Cursor location – is the visible location of the cursor in the window.

- Tick – is the instance in time that the app calculates the new cursor location in the browser window and displays it. Ticks will occur at the rate of 10 or 60 hertz.

- Scene – is the svg element in the browser that contains all visual elements, start, cursor, target and obstacles.

Strategy

- At the appropriate time, the app hides the default cursor, replacing it with the app’s cursor, an SVG circle.

- The app continuously monitors the pointer location and the browser window size.

- At each tick, the app updates cursor location based on the pointer location.

- At each tick, the app determines if the cursor is in the target or collides with an obstacle, and then draws or invokes the appropriate response.

If the cursor is in the target then the trial is over.

If the cursor collides with an obstacle then we want the app to perform the appropriate consequences (or simulation) that we wish to evaluate.

Challenges

A challenge that exists for all user interfaces in the browser is that the window size is not fixed and can change at any time. This is particularly challenging for us because we are drawing the entire scene and can not use the standard tools provided by the browser and HTML. To overcome this challenge we will express the “general” arrangements and positions of the scene elements, such as the start, cursor, target, and obstacles, in “nominal” units. Consequently, the first step in the tick calculation will be to convert nominal units into screen units.

A challenge that is specific to an application manipulating the cursor is that the cursor location and pointer location will deviate. The deviation can become large enough such that the pointer location is outside of the browser window. When this occurs the user will lose control of the cursor using the mouse. There are no good solutions for this problem. We could reject the collision simulations that may cause large deviations, or we will need a way for the user to regain control of the cursor using the mouse.

Implementation

This tutorial will implement two versions of collision simulations through a series of steps.

Clone the repository. In the appropriate directory on your home machine, enter in the terminal:

git clone https://github.com/2025-UI-SP/obstacle-avoidance.git cd obstacle-avoidance

Step-1

In the first step we just set up the basic scene, the cursor and target. The mouse is used to move the cursor and the app identifies if the cursor is in the target.

Before running the app we need to fetch all the tags and checkout the first step. In the project directory, enter in the terminal:

git fetch --tags git checkout Step-1

To run the app, we need to install the package and then run in development mode. Enter in the terminal:

npm install npm run dev

Now open your browser in port 5137. The cursor is white and the target is blue. The target will turn green when the cursor is inside the target. During development, I like to see the default cursor along with the app’s cursor. Later in the development, I will show how to run the application with the default cursor hidden.

As I describe the code, I expect that you will look at the code in your IDE. I will try to indicate the code snippet locations as I describe the code. Implementing was initiated using the Vite “create-app”:

npm create vite@latest

following the prompts, selecting “React and JavaScript” and the “React Compiler”.

https://vite.dev/guide/#manual-installation

I like to first look at the dependencies in the package.json to get a sense of what libraries are used. The dependencies used to run the app are just “react” and “react-dom”. That is nice, it is good to have a short dependency list, so there is not too much to maintain. The development dependencies list is longer, but it is primarily using “vite”, and a bunch of “types” and “eslint”. We need the Vite libraries to bundle the JavaScript code and serve the app. React probably needs the “type” libraries.

Code Organization

To get the general idea of the organization of the app, we’ll follow the React components starting with index.html. As is traditional with Vite apps, index.html is located in the project root. There is nothing new in index.html. Its main role is to provide the “root” div for the React components.

Rollup, the JavaScript bundler (https://rollupjs.org/) looks for the main.jsx in the src/ directory. The main.jsx only creates the “root” for the React app and specifies using React’s StrictMode. It imports the top most React component, App.jsx, from the app/ directory.

The App component is used to wrap the AppProvider around the Scene component. AppProvider.jsx is located alongside the App.jsx in the app/. It just provides access to the reducer for the entire app. You can read more about a Provider at

https://react.dev/learn/scaling-up-with-reducer-and-context

The app/ directory also contains the “reducer.js” file. We’ll return to it when we study the logic of the app.

The Scene component code is located in the “../features/scene/” directory. I like to use feature based directory structure rather than type based. You can read why at

https://profy.dev/article/react-folder-structure

The Scene is the component that draws all the visual components of the app, the cursor and target. So it is our first feature for our application.

Scene.jsx has a lot of code, so it is essential to organize the code in the file. The general organization of Scene is

import specifications

Constants declarations

Convenient function definitions

export default function Scene(){

dispatch call

state call

Listeners

useEffect(() => { // the initializing useEffect

...

}, [ ] )

useRef

state variables to describe the component

and preparing the children components' props.

return (

// all the children components

)

}

This organization is syntaxily correct and associated code snippets are adjacent to each other. So I encourage you to use this organization for your react components. The imports have to appear at the top of the page. Constants affect the entire code and developers typically want fast access to them. Any complex component will need dispatch and state, so their declarations are located just below the component declaration. Listeners need to be defined before their use. The useEffect sets up all the listeners. The useEffect has no dependencies, so I call it the “initializing useEffect” because it only runs when the component is first mounted.

https://react.dev/learn/synchronizing-with-effects#step-3-add-cleanup-if-needed

This app uses “useRef” to get a reference to a node.

https://react.dev/learn/referencing-values-with-refs#refs-and-the-dom

So it is located near the component’s “return”. Props can become long and complex, so I like to prepare them just above the “return”, so that they separate before the “return”, but can still be easily referenced.

Scene’s return is a series of encompassing devs, each serving a single purpose. The “page” div provides the background styling for the scene. The “sceneContainer” is used for the reference to the DOM. The scene svg element contains all the visible components. We want the scene svg to fill the entire browser window so its height and width need to be specified. The Target and Cursor components are part of the scene, so their files are located in the “features/scene/” directory. Both Cursor and Target are circle svg. Their code is simple, and you study them on your own. We will return to the Scene component when we study the logic of the application.

We have skipped some files. The first is input.js located in the src/ directory. The file input.js is all the inputs to the app that I or the client might want to change. Its formatting is similar to a JSON and should probably be a JSON, but using JavaScript object formatting is more tolerant, permitting comments, and quick to implement for the development of the app.

The structure of input.js is basically divided between “geometry” and “styles”. The geometry property is the nominal dimensions. You can interrupt the geometry by imagine that the nominal scene size would be 700 pixels and then all the other dimensions are relative to 700, the nominal scene size. The “styles” property is obvious. It specifies the styles for all the visual elements in the scene.

We have also skipped the CSS files. We want the scene to fill the entire browser window, so all the encompassing elements must be styled at 100% height. The main.css specifies this style for the html, body and root elements. All of them are necessary.

The scene.css likewise specifies the height and width for the page and sceneContainer div at a hundred percent. The scene div height and width are not specified in scene.css because it is specified in-line in the scene svg. We will also want to hide and show the default cursor, so scene.css specifies two CSS classes with “cursor” properties, hidePointer and showPointer.

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS/cursor

Note this Step cannot hide the cursor, so the hidePointer and showPointer rules are a bit premature.

App logic

We have looked at all the files for the application. Let us now study the logic of the application. For React apps nearly all the logic is specified in the reducer. So look at the reducer.js file in the app/ directory. At the top of reducer.js is the specification of the initialState. I put the initial space at the top of the reducer because I use it to reference what is in the app state and how it is structured. Consequently but strictly necessary, the initialState variable should be up-to-date and be accurate. I also document it well. Following the initialState specification is the reducer function. It is basically a giant switch on the action types. The “bndRectChange” and “pointerMove” actions just update their respective state variables. We will study how they change when we look at the Scene component again. For now just study how the nextState is constructed. The object literal used is to assure that that a new object state is created.

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Guide/Grammar_and_types#literals

It is important that nextState be a new object because that is how React determines if the state has changed. The spread operator is used to fill in all the state variables that have not changed.

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Operators/Spread_syntax

Especially note, that the entire hierarchy of the state variable must be created new and spread up to the changed state variable. Finally, the changed state property uses an “object shorthand” to specify the property name and value, and replaces the old state property value.

Now we study the “tick” action. The “tick” action uses the “setTickState” function to separate the code from the switch. The setTickState function separates specifying the state changes into three steps. First it calls the “getDrawState” function to calculate all the location and dimension that might have changed due to the pointer moving or browser window size change, and then it determines any styling change due to the cursor movement by calling the “getInTarget” function. Finally it constructs the nextState and returns it.

Let us study Scene components for how actions are dispatched. In Scene.jsx, notice that the initializing useEffect adds an event listener for browser events, resize and pointermove, using the “registerListener” helper function. The listeners, onBndRectChange and onPointerMove just prepare the action, specifying the type and “payload”. Tick action is dispatched by onTImer which is the callback function from the setInterval call made by the initializing useEffect.

Now we study the “getDrawState” function. I located this function in the engine/ directory adjacent to the Scene.jsx file, so that it is handy during development. It perhaps would have been more logically located near the reducer.js file. Nevertheless it is the basic engine for the scene.

First, getDrawState deconstructs the nominal dimensions that it needs from inputs.js and the state variables it needs from state. Then it calculates the conversion from the actual window sizes and the nominal scene size using the getSceneToPage help function. It also calculates the page center because we will locate the target centered horizontally in the browser window. Finally it calculates the cursor location and target location using respective moveCursoLoc and getTargetLoc functions. The movePointerLoc function is rather silly at this point because it just returns what is passed to it, pointerLoc, but it will become more complex when we manipulate the cursor. The getTargetLoc function is a little more complex because we have to use the conversion from sceneToPage.

I will not discuss the helper functions in drawUtils.js. They are a collection of functions that I have found useful in prior application development. You can study them on your own.

That is it. Be sure to study how the code is organized and the app logic is implemented. Step 2 will add new features which will make the code more complex.

Step-2

In step 2 we want to make the app resemble more like trials for cognitive test by:

- Adding an Intro Modal that explains what to do.

- Adding a start circle that the user clicks in to start the trial and show the cursor.

- Adding an End Modal after the user clicks in the target and showing the time acquiring a target.

- Performing another trial after clicking in the start circle

Checkout Step-2 tag by entering in the terminal:

git checkout Step-2

Before running the app, let us look at the package.json. New dependencies have been added to the app “bootstrap” and “react-bootstrap”. These are for adding the modals. Consequently before running the app we need to run npm install again to download modules. In the terminal enter:

npm install git checkout Step-2 npm run dev

Running the app, you are presented with a modal explaining how to start the trial. After clicking the “Start” button in the modal, you need to click in the start circle at the bottom of the window, and the cursor appears. Now you can either drag or move the cursor to the target. In the target you either need to click or release the drag to finish the trial. A modal appears thanking you and showing the time in msec to acquire the target. You can click the “Try again” button to run another trial.

If you wish to try the app without the default cursor always showing you can comment out line 170 in Scene.jsx. Try it.

// isPointerVisibleFalse = DEVELOPMENT ? "showPointer" : "hidePointer" // COMMENT OUT for development with hidden pointer

Code Organization

The code organization has not changed much except that there is a new features subdirectory, experiment/. The role of the Experiment component is to control the overall experiment, displaying the modals and controlling the visibility of the scene component before and after the trial.

Experiment is the child component of the App component, and Experiment contains the IntroModal, EndModal and Scene components.

IntroModal and EndModal import react-bootstrap Modal and Button. They are very similar but have different props which we will discuss during the code logic section. You can read about Modal at

https://react-bootstrap.netlify.app/docs/components/modal

It is a static modal with animation. The props are defined in the modal api section

https://react-bootstrap.netlify.app/docs/components/modal/#api

The Button documentation is at

https://react-bootstrap.netlify.app/docs/components/buttons

The props for buttons are defined in the api section at:

https://react-bootstrap.netlify.app/docs/components/buttons#button

The “onHide” prop is the callback for the onClick prop for the button.

The only additional change to the directory structure is the addition of the Circle.jsx and removal of the Cursor.jsx in the features/scene/ directory. The start circle and cursor are similar; they just styling changes, so they use the same component definition.

The input.js file grew because of the addition of the start circle and the modals. The text for the modals appears in their properties. The nominal y position for the start location is defined in the geometry property.

App Logic

Again we start studying the app logic by looking at the initialState in reducer.js. The experiment property has boolean properties for showing the IntroModal and EndModal. The obvious additions to the scene state properties are the start object, isStartVisible, isPointerVisible, isCursorVisible, isTargetVisible, startTime and endTime.

The less obvious additions to the initialState are the pointLoc and corresponding pointerOrigin, and cursorLoc and cursorOrigin. I will explain them later in our study of application logic.

The other significant change is the introduction of stages for the app. The app logic and state has become complex enough to keep track of the stages the user progresses in the application. The stages are:

- INTRO – which is when the intro modal is shown and before the user clicks in the start modal.

- MOVING – which is when the cursor shows and the user is moving the cursor

- END – which is after the user clicks in the target and the EndModal shows.

In summary, the critical phase change is transitioning to the MOVING stage, because during this stage the pointer location needs to be tracked and the cursor location updated. During the INTRO and END stages only the pointer location needs to be tracked.

The switch in the reducer has grown. Many of the new actions are obvious. The less obvious reductions are pointerDown and pointerUp actions. The pointerDown case will only fire if the app is in the INTRO stage and the pointer location is in the start circle. The getInBoxCircle is not the best name for the function that determines if the pointerLoc is in the start circle. The pointerDown action then changes the stage to MOVING, sets the pointerOrigin to pointerLoc and the cursorOrigin to the start location. It also shows the cursor and hides the pointers. Finally, the startTime is recorded. A final note about the pointerDown case is the “else” statement which sets nextState as state, the current state. This must be done because the reduction must always return the state.

The pointerUp case is very similar except that now it checks that the stage is MOVING and checks that the cursor is in the target state. The stage is changed from MOVING to END and the endTime is recorded.

The tick case has not changed. The only changes to setTickState are additional objects destructured from the getDrawState return, and adding the objects to the return.

We progress to the drawState function in scene/engine/ directory. Besides locating the cursor and target, it also needs to locate the start location in the getStartLoc function. But this is very similar to the getTargetLoc function.

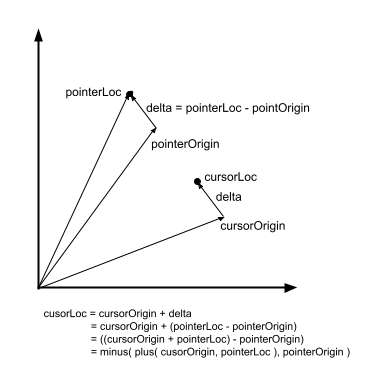

The moveCursorLoc function has changed. First we should describe the desired interaction. After closing the IntroModal, the user should use the pointer, default cursor, to click in the start circle. Despite where the user clicks in the start circle, we want the cursor to appear in the center of the start circle and the pointer to disappear. This implies that there is a discrepancy between the cursor and the pointer locations, and we can not just use the pointer location for the cursor location as the pointer moves. To understand the calculation in moveCursorLoc study the figure below.

Delta is the difference between the new pointer location and the fixed pointer origin, the initial pointer location when the user clicks in the start circle. This delta is added to the cursor origin. Note that the figure represents victor algebra. Simple algebra reduces the formula that is used in moveCursorLoc.

To finish our study of the application logic, let us look at the Experiment component which controls the over application progression. Experiment.js is located in the features/experiment/ directory. To follow the progression of the app we should first look at the initializing useEffect. It dispatches actions to show the IntroModal and dispatches actions to hide all the scene components. It finally set the app stage to INTRO.

The functions onIntroHide and onEndHide are listeners for when the buttons to close the modals are clicked. When onIntroHide is called, it hides the IntroModal and shows the Start and Target components of the Scene. Note that the Cursor is not shown and the default cursor is still visible. Likewise when onEndHide is called, it dispatches actions to hide the EndModal and shows the Start and Target, but not the cursor, and sets the application stage to INTRO. So that the user can perform another trial.

That is it. Be sure to study the application logic before study step 3 code because step 3 will become more complicated.

Step-3

In step 3 we want to add obstacles, detect the collision with the obstacle, invoke the consequence for colliding with the obstacle. In step 3, the consequence is freezing/pausing the cursor, showing a modal informing the user that a collision with the barrier has occurred and that they should click on the cursor to resume the trial, and then the obstacle is hidden.

Checkout Step-3 tag by entering in the terminal:

git checkout Step-3

Before running the app, look at the package.json. No dependencies have been added from step 2, so we can run the app without installing. In the terminal enter:

npm run dev

Code Organization

The code organization has not changed much except that the experiment feature replaces the IntroModal with the SimpleModal, so that the Modals that appear at the introduction of the trial and after a collision can use the same Modal code. Also the Obstacle component has been added to the scene which is composed of an array of Rect (Rectangle) components. You may want to look at Obstacle.jsx; it uses Array.map to construct the Obstacle component.

In input.js, there is a new property called “collision”, which specifies which collision interaction should be used, in this case “withModal”, by setting “using” property of “withModal” to true. This is set up in anticipation that additional collision interactions will be implemented. Also the text content for the collision modal is specified in the “collisionModal” property.

In addition, in the geometry property, the nominal obstacle location and dimensions are specified in the “nomObstacle” property. The obstacle is a horizontal line with constant height and composed of segments. So it needs the “y” location and “height” dimension, and array of left and right locations, xL and xR. Also the style of the obstacle is specified in the styles property.

I have refactored the Experiment component. The list of dispatches in onIntroHide, onEndHide, and initializing useEffect was rather long so I combined them into a single action, startTrial for onIntroHide and onEndHide, and initializeExperiment for the initializing useEffect. Combining dispatch also eliminates the annoying jump that the cursor made when the user clicked in the start circle because the cursor appears at the same rendering instead of separate rendering. We also need to specify the dispatches for when the collision modal is closed in onCollisionHide. In this case, I did not combine the individual dispatches into a single modal because there are only two dispatches.

Combining the dispatches required defining the combined actions in the reducer.js. I kept the individual actions in reducer.js just in case I should need them in the future implementation, but moved them below the combined actions.

App Logic

Again we start studying the app logic by looking at the initialState in reduces.js. The experiment property has the additional property, showCollisionalModal. Also the scene property has additional properties for locating and showing the obstacle, obstacle is for specifying the location and dimensions of the obstacle, also specified are isInObstactile and isObstacleVisible.

More interesting is the refinement of the stages for the app. There are two refinements. The first improvement is that reduce.js exports constant (const) for the stages. This has two consequences. The list and sequence of stages can be explicitly stated in recducer.js. The second consequence is the IDE can assist in prompting the stage when we start typing it. The second improvement in that several stages have been to incorporate the interactions of the collisions. The stages are

- INITIALIZE – for when the useEffect show shows the IntroModal.

- START for after the user has closed the IntroModal and is moving the pointer to the start circle.

- MOVING – for when the cursor shows after clicking in the start circle.

- FIRE_PAUSED – for when a collision has just occurred. This stage last for a single tick and is used to invoke a PAUSE in the cursor motion.

- PAUSED – for when the collision model is shown after and the user is moving the pointer to the cursor location.

- MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED – for when the user clicks the cursor after the collision and causes the obstacle to disappear.

- END – for when the user clicks on the target and the EndModal is shown.

Not all the stages are explicitly used, but it is still important to keep them in mind. In particular, FIRE_PAUSED is not used in this collision interaction; it will be used in the next version. Also MOVING and MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED have the interaction.

The pointerDown action has grown to include clicking in the cursor after a PAUSE (i.e. collision has occurred) this is implemented using an enclosed switch in the pointerDown case. In both the START and PAUSE cases the pointerOrigin and cursorOrigin are updated. In addition, the START case changes the stage to MOVING and the PAUSED case transitions the stage to MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED.

The pointerUp action is for dispatching the action after the user has clicked on the target. There is really no interaction difference between MOVING and MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED so the two constants are combined into a single “or” boolean, isMoving. The isMoving boolean is used in the pointerUp if statement with the getInTarget boolean function.

The tick action has not changed, but the getStageTransition function is added in reducer.js and has the additional task of detecting if a collision has occurred. It then transitions to the PAUSED stage. Note this version of the app skips over the FIRE_PAUSE stage.

The drawState function in features/scene/engine/drawState.js has the additional task of locating the obstacle in the getObstacle function. It is very similar to the getStartLoc and getTargetLoc, but uses the Array.map to locate the segments.

The moveCursorLoc has two cases to handle when the app is in the MOVING/MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED or PAUSED stages. During the MOVING/MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED the same calculation is used as in the previous version of the app. The PAUSED case freezes the cursorLoc at the updated cursorOrigin.

That is it for the application logic for this version of the application. Be sure to study the application logic because it will get more complicated in the next version of application.

Step-4

In step 4 we want to change the collision interaction. Instead of using a modal and freezing the cursor. The app will not show the modal, but will freeze the cursor for a fixed time. The app will use a setTimeout to freeze the cursor rather than the user closing the modal and clicking on the cursor. This implementation is a particularly subtle implementation.

Checkout Step-4 tag by entering in the terminal:

git checkout Step-4

Before running the app, look at the package.json. No dependencies have been added from step 3, so we can run the app without installing packages. In the terminal enter:

npm run dev

Be careful while using this collision interaction version because it is easy to cause a discrepancy between the pointer and cursor origins so that you lose control of the cursor while trying to reach the target after a collision. Do not move the mouse much after colliding with the obstacle.

Code Organization

The code organization has not changed. The Experiment component still has the CollisionModal and onCollisionHide listener even though this version will not use it because we want to change the collision interaction by just changing the input.js collision property.

In input.js, the collision property has additional property “fixedDelay” with the “using” property set to true while the “withModal” option’s “using property” is set to false. I wish there was a better way to specify the collision property, but I also want the property to show all the possible collision interaction options. The “fixedDelay” option needs to specify the “pauseDelay” property.

Nothing else has changed organization.

App Logic

Again we start studying the app logic by looking at the initialState in reduces.js. Nothing has changed in the initialState.

Before proceeding with studying the application logic expressed in reducer.js, we should discuss the challenge implementing the collision interaction using a fixed delay. The reducer should be a “pure” function. See

https://react.dev/reference/react/useReducer#parameters

A pure function implies in addition to “same input same output” that there should not be any side effects. Consequently, we cannot use setTimeout in the reducer. The setTimeout must be called in a component distinct from the reducer. In this case, the Scene component is the best location to call setTimeout. We face an additional constraint. Scene cannot just watch for the stage state variable to call setTimeout because the callback function for the setTimeout will dispatch an action. Scene’s rendering must be synchronous or immediate, and the setTimeout is essentially asynchronous, so we must use a useEffect. The most similar usage example of this kind of useEffect is when an application makes a fetch to get data. See

https://react.dev/learn/synchronizing-with-effects#fetching-data

With that in mind look at getStageTransition in reducer.js. When the cursor isInObstacle and the stage is MOVING then stage is set to FIRE_PAUSE. Now look at the code in the Scene component:

/*

* This code detects stage change to FIRE_PAUSE

* and then starts a timeout to delay for the PAUSE stage.

*

* Note must use "useEffect" because the timeout

* implies an asynchronous dispatch.

*

* Note that fire is the dependent variable.

* It will change from false to true when

* the stage becomes FIRE_PAUSE.

*/

const fire = state.scene.stage === FIRE_PAUSE;

useEffect( () => {

setTimeout(

endPause,

input.collision.fixedDelay.pauseDelay,

)

dispatch({

type: "firePause"})

}, [fire]);

/*

* endPause is the callback for the timeout.

* It dispatches the actions for the state changes

* at the end of the pause delay.

*/

const endPause = (timerId) =>{

const isObstacleVisible = false;

dispatch({

type: "setObstacleVisible",

isObstacleVisible

});

dispatch({

type: "setStage",

stage: MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED

});

}

When the Scene renders just after the stage is changed to FIRE_PAUSE, the variable “fire” will change to true. The “fire” variable is the useEffect’s dependency, so the useEffect will be invoked which calls the setTimeout with the “endPause” callback and dispatches the “firePause” action. In the reducer, the “firePause” action just changes the stage to PAUSED. So the FIRE_PAUSE lasts just one tick, time enough to setTimeout. After the delay, endPause dispatches setObstacleVisible action with isObstacleVisible false and dispatches the setStage with stage set to MOVING_AFTER_PAUSED. After the delay ends, Scene hides the obstacle and the user can move the cursor.

That is nearly all the implementation changes for Step-4.

Study this collision interaction and its implementation. Consider how you could remedy the issue of large discrepancy between the pointer and cursor origins and think of alternative collision interactions.

Conclusion

The lesson learned in this tutorial is implementing an React app is easy if you:

- Organize your code and break it up into features and small pieces of code.

- Keep all your application logic in the reducer.

- Explicitly describe the app structure in the initialState variable.

- Explicitly state the major application stages/phases in the reducer by exporting constants.

- Keep the app synchronized by using useRef and useEffect properly.

- Develop incrementally and constantly test the user interface.

- Gather all the input variables in an input file.

- Constantly refactor during development to keep the code concise and clear.